When was the last time you took a drive to Chloride?

If you’ve never been, just the ride alone is scenic enough to make it worth your while. All weather roads that wind their way through breathtaking mountain vistas, vast high desert spaces stretching on for miles, and puffy-cloud-studded blue skies galore. You’ll pass through Cuchillo with the old white church and Winston with its well-known General Store. You may even run into some ranch cattle crossing the road here and there, and if you look closely, a roadrunner may catch your eye (as in the above photo).

So, what’s the draw of making that turn toward Chloride? Aside from being a somewhat under the radar “gateway to the Gila” (yes, the roads are rough but it’s true!), it seems like there’s always something new underway in this historic gem of a ghost town that’s been visited, documented, and featured in several publications and documentary-style shorts through the years.

I’ve lived in Sierra County for a little over a year now, and this was my first time exploring this well-preserved slice of New Mexico’s history and meeting its devoted caretakers and stewards, Don and Dona Edmund and their daughter, Linda Turner. I spent a full day seeing the sights and soaking it all in. With only 11 current residents making their homes in Chloride as of my visit, it was quite a trip just to imagine how it must have looked, sounded, and felt to be amidst the town’s silver mining madness over 100 years ago.

At one time hustling and bustling with around 3,000 folks who came from all over to try and strike it rich—or just live simply—out west in the late 1880s, Linda (our very friendly and knowledgeable tour guide) says we would’ve seen saloons, dance halls, eateries, boarding houses, miners, tradesmen, blacksmiths, businessmen, and a community of folks who may have appeared gruff on the outside but were known to look after one another when it came to basic needs and dealing with out of town cowboys and miners who got a little too rowdy (a.k.a. they tied ‘em to the “Hanging Tree,” pictured below, and let them cool down overnight and wake up in the morning chained—not hung—to said tree, smack in the center of town). And yes, like most mining towns in the west, this one is believed to have had its backwoods “cribs” where the ladies of the night did what they had to do to survive.

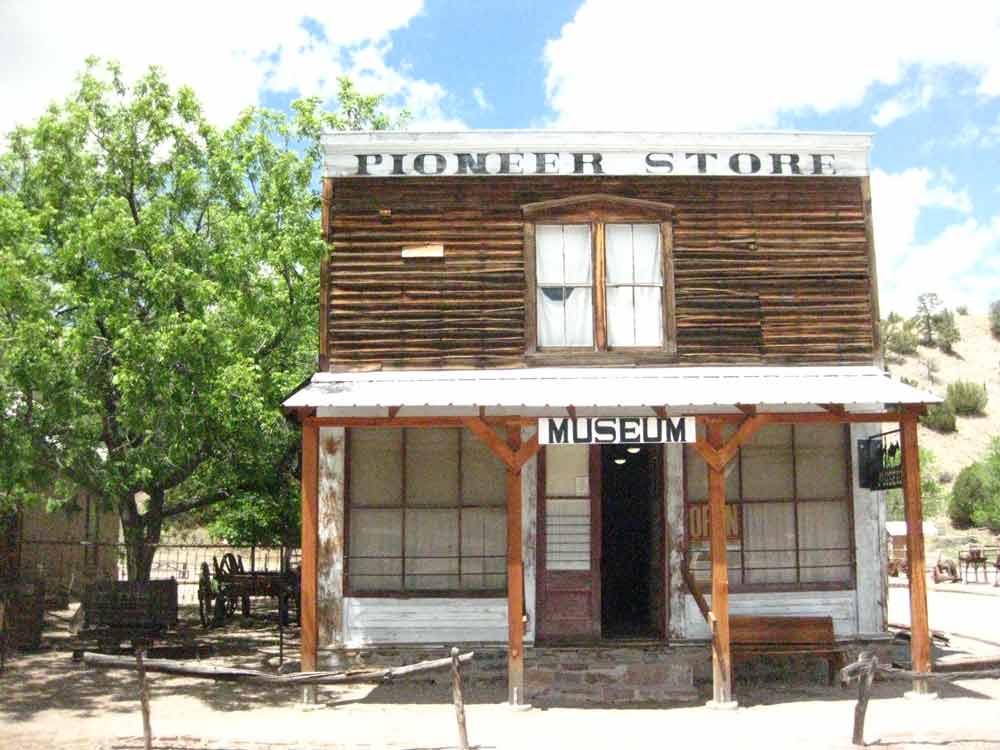

What you’ve most likely heard of already is the most prominent feature of present-day Chloride: the Pioneer Store Museum. Built in 1880 by a man named James Dalglish as a one-stop shop for all your food, self-care, household good, U.S. postal service, and work-related needs, the store remained under his ownership until 1897, when he moved his family to Hillsboro (another historic town on the Geronimo Trail Scenic Byway).

In 1908, after leasing the store for several years from afar, Dalglish sold it to the U.S. Treasury Mining Company, which was owned and operated by the James family. The new owners kept it stocked and serving the people of Chloride for a number of years, but with their business dwindling and the town rapidly losing its residents, the James family closed up shop in 1923. Lumber and tin were used to board up the doors and windows, and all the merchandise was left sitting on the shelves.

Amazingly, when the Edmunds purchased the property from the youngest son of the James family in 1989 and stepped inside the store for the first time in almost 70 years, they discovered bottles, boxes, trinkets, and treasures galore—most of them perfectly in tact. Yes, they had to shoo away rats and bats and do a complete restoration and cleaning of the property to get it ready for public appreciation.

But ultimately, the building had remained standing for several decades following its closure, “sealed like a giant time capsule,” as Linda described it. And once the sorting, scouring, and repair work was done, there remained a significant assortment of artifacts that makes an old west history lover like myself feel like a kid in a candy store.

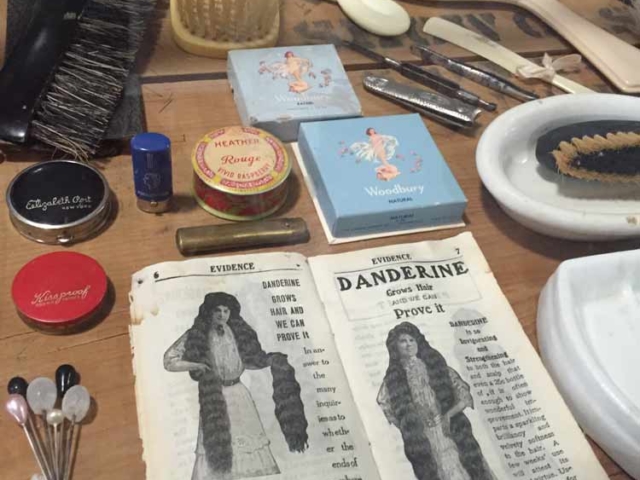

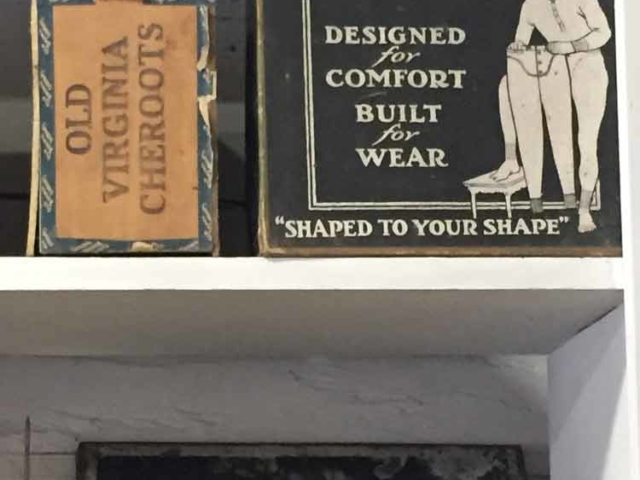

As you wander around the museum, you can marvel at the fact that much of the original building—floors included—is what you are seeing when you walk through the Pioneer Store today and ogle the fascinating assortment of odds and ends that have stood the test of time. There are the basics, like clothing, shoes, boxes of underwear, hair-care products, large cell batteries, stamps, cookware, household tools, liquor, and foodstuffs.

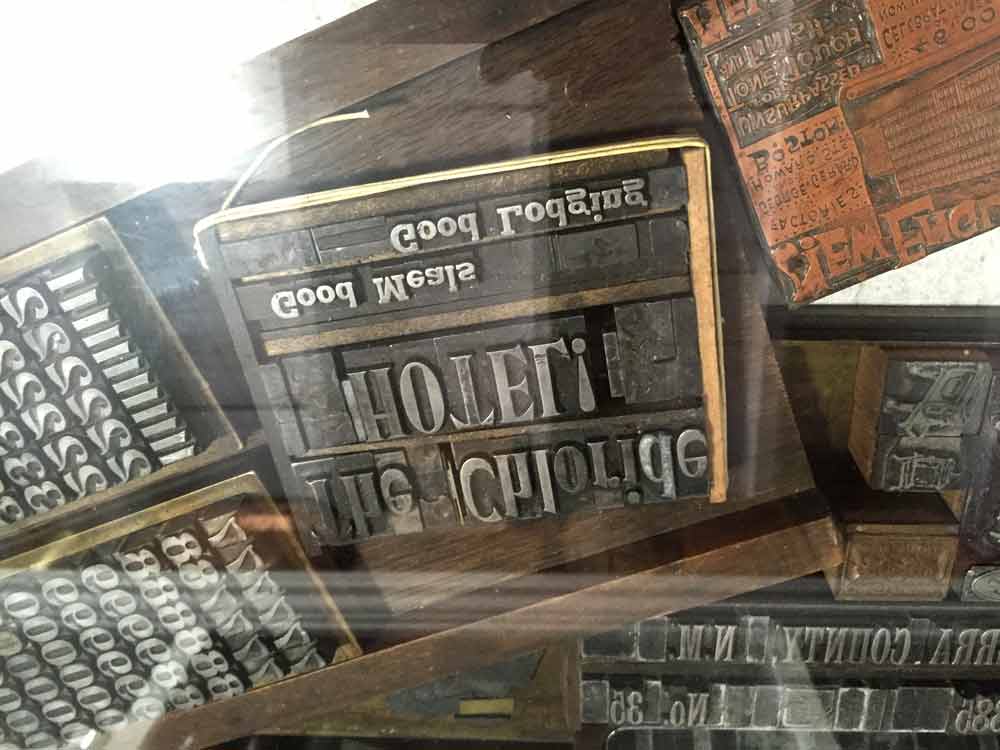

And then there’s the giant vintage radio that belonged to one of the women in town who liked to broadcast local news to the neighbors, as well as my personal favorite: typesetting tools and printing blocks from back when the upstairs of the building housed the Black Range Newspaper from 1882 to 1896. The presses were relocated to Hillsboro when Chloride’s silver boom died out, but a few of the original Black Range printings are preserved and on display in the museum’s document gallery (sweet!).

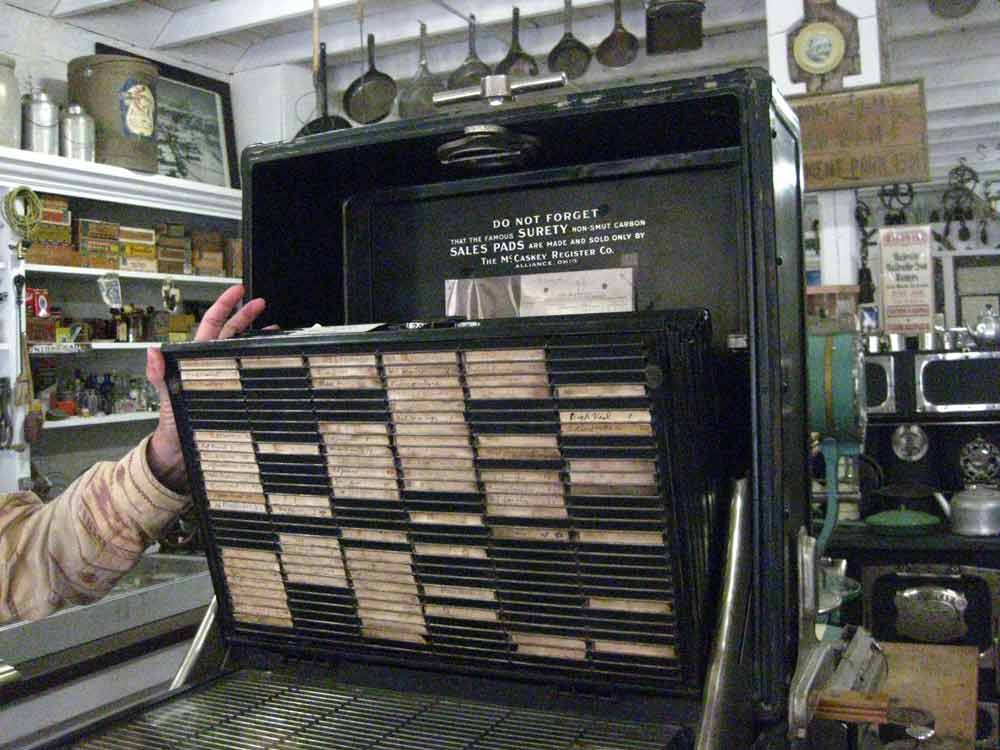

I also really loved the antique fireproof credit machine and cash register in one, which was not only beautifully designed and constructed, but also kept a detailed and highly organized paper trail of all customer accounts and general store business affairs. (People owed some pretty big debts to the store back in the day!)

Another mildly entertaining observation was to take note of the food and beverage companies that were alive and kicking at the turn of the century: We saw Folgers and Maxwell House coffee cans, boxes of Quaker Oats, and a quarter-full bottle of Jim Beam Whiskey, just to name a few.

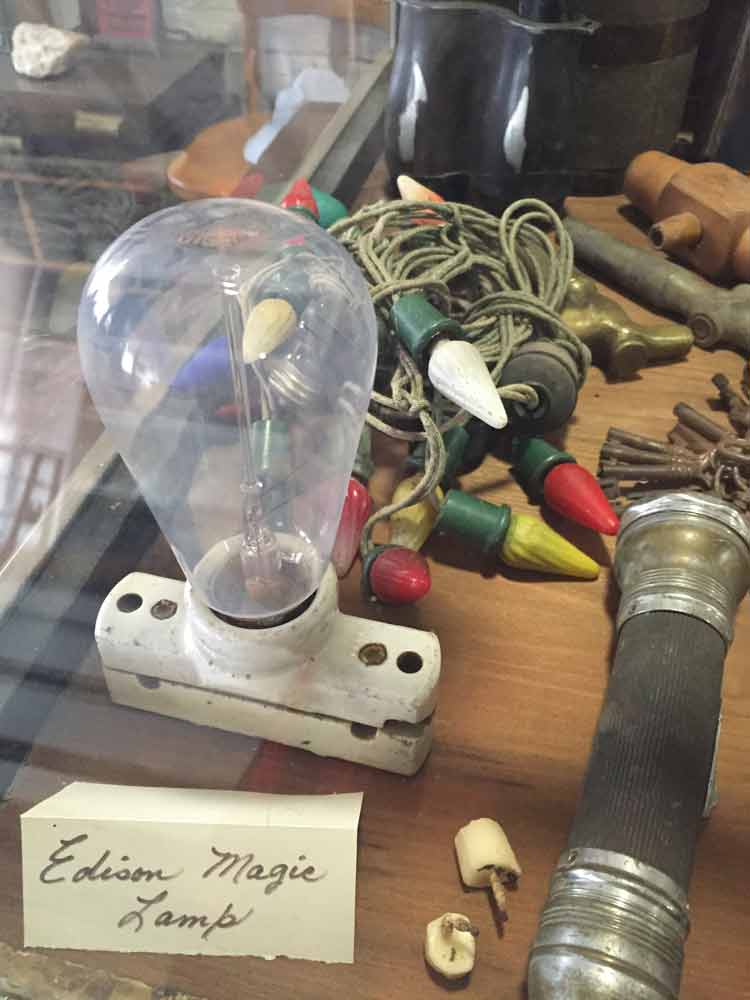

One lesser-known tidbit Linda shared involved a man by the name of Thomas Edison (yep, that one). Apparently, Edison embarked on an exploratory research assignment that took him through several mining towns out west, including Chloride. While in town, he met and hit it off with a local resident by the name of Henry Schmidt. Schmidt, who was one of the original town surveyors and settlers in 1880, was a tinkerer and inventor in his own right, though far in body from the bright lights and big investors of the cities back east.

He and Edison had a great deal in common, and they became good friends through the years, with Edison making several return trips to Chloride to compare notes and spend time with Schmidt. On one of those trips, he left one of his latest inventions with Schmidt. It remains in the Pioneer Store Museum today, dubbed the Edison Magic Lamp.

An interesting aside to the Edison story is that Henry Schmidt, who lived in Chloride until his dying day, now has one of his self-made X-ray machines, the construction of which was influenced by Thomas Edison, on display in the University of Texas School of Medicine in Galveston. And according to Linda, when Henry’s son Raymond passed away not too long ago, four hand-wound electric motors were found in the home—two labeled Thomas A. Edison, Menlo Park, New Jersey, and two labeled Schmidt & Edison, Chloride, New Mexico.

Appropriately, these were sent to Henry’s great grandchildren as family heirlooms and keepsakes. However, Linda would love to one day see them show up in Chloride again. “Hopefully, if they ever decide they don’t have a place for them, they’ll think about me, and bring them back to the museum here in Chloride,” she added with a smile.

Beyond the Pioneer Store Museum, a Chloride attraction that has yet to become a reality but is in the works is the Cassie Hobbs house. As an avid reader of pioneer women’s stories, I was instantly intrigued by Cassie, one of 12 children who was born and grew up in a covered wagon until age 14, and then married a cowboy named Earl at 16 and traveled with him from camp to camp for many years. She spent much of her life in tents and wagons, and along the way learned how to build custom-made furniture and make all of their clothing from scratch every time they set up camp.

She eventually settled with her faithful rambling man in Chloride, where she continued to craft fine furniture, intricately woven shoes, and colorful outfits for herself and her neighbors from the comfort of her home, all while growing a vegetable garden full of food and regaling locals with tales of tougher times. As Linda said, “She epitomizes the pioneer spirit.” And since her passing, the Edmunds have been working toward turning Cassie’s home into a museum that preserves and portrays her countless creations and pioneer woman ways.

I could go on—about the stories Linda shared, the handful of additional historic buildings that are currently in restoration and will eventually be added to the Chloride collection, and the countless hours the Edmund family has spent rescuing and restoring these ancient relics.

But one important point must be made: Did you know this entire operation is run by donation only? I sure didn’t. I was actually quite shocked to learn that the New Mexico Historical Society does not help in any way to fund their work, and so Don, Dona, and Linda have relied entirely on patron offerings and fundraisers since they first opened the museum doors over 20 years ago.

Consider helping the history of New Mexico’s boomtowns live on by supporting their cause, be it via an in-person visit and donation or a check in the mail. Or, perhaps a more indulgent way to contribute to the preservation of Chloride is to plan on staying in one of the cozy cabins* available by the night to weary travelers. I got a peek inside, and I can definitely see planning a getaway down the road. Soaking in the rich history of a restored rustic cabin from the late 1800s combined with the comfort of a modern mattress? Plus star-filled night skies free of light pollution and an opening to the Gila Wilderness within walking distance?

*More information is available at the Pioneer Store Museum website regarding current hours and buildings open to the public, rental cabins, and a thorough history of the town and its residents.

Comments are closed.